Introduction – The Dilemma of Distributed Transactions

Imagine you are developing a classic e-commerce application. A customer clicks “Buy” and a process is initiated in the background that consists of several steps:

- The order is created in the database.

- Payment via a payment provider is authorized.

- The stock of the purchased product is reduced.

In a monolithic architecture where all modules access a single database, this is a common task. We package these three operations into a single database transaction. With a simple @Transactional annotation we ensure that the ACID principle (atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is preserved. Either all three steps are successful, or none of them are saved permanently. If the payment fails, the order creation and inventory reduction will also be rolled back. All or nothing. Simple, safe, proven.

But what happens when our application grows and we decide to use a modern microservice architecture? Suddenly, instead of a single system, we have several specialized services: an ‘Order Service’, a ‘Payment Service’ and an ‘Inventory Service’. Each of these services has its own independent database.

The logical business operation of “place an order” now spans three different systems. A cross-database 2-phase commit (2PC) would be a solution in theory, but in practice it is often too complex, slow and poorly scalable. The cozy security of a single transaction is gone.

Here we are faced with the central problem: How do we ensure the consistency of our data across service boundaries? What happens if the ‘Payment Service’ reports an error after the ‘Inventory Service’ has already successfully reduced the inventory? We would have one less product in stock, but no appropriate receipt of payment - an inconsistent situation that is damaging to business.

The SAGA Pattern was developed precisely for this dilemma.

I’m glad the introduction fits. Then let’s get straight to it and explain the heart of it all.

Here is the draft for the second section in which we conceptually introduce the SAGA Pattern.

What is the SAGA Pattern? A conceptual introduction

The SAGA Pattern solves the problem of distributed transactions by breaking long, comprehensive business logic into a sequence of individual, local transactions. Each microservice is only responsible for its own atomic transaction. When a local transaction is successful, it triggers the next step in the chain.

Sticking with our e-commerce example, the “place order” saga would look like this:

- Step 1: The

Order Servicecreates the order with the statusPENDING(Local Transaction A). - Step 2: The

Payment Serviceattempts to process the customer’s payment (Local Transaction B). - Step 3: The

Inventory Servicereduces the inventory for the ordered product (Local Transaction C).

The key point is: Each of these steps is consistent on its own. The ‘Inventory Service’ knows nothing about payments, and the ‘Order Service’ doesn’t care about inventory. The system as a whole ultimately reaches a consistent state, which is referred to as “Eventual Consistency”.

By the way, the concept is not a brand new invention of the microservices era. It was already described in a 1987 paper by Hector Garcia-Molina and Kenneth Salem to ensure consistency in “Long Lived Transactions” (LLTs).

There are two established approaches to implementing a saga:

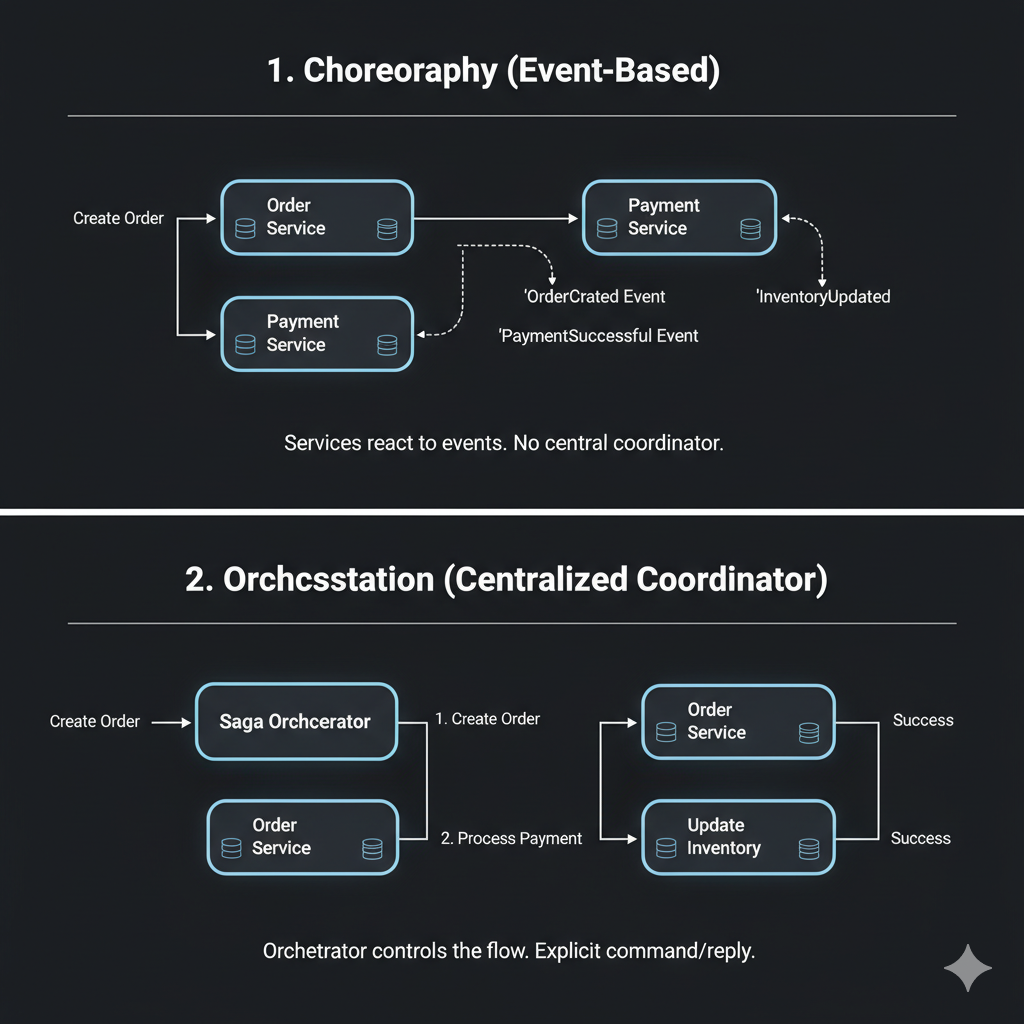

1. Choreography (Choreografie)

Imagine a group of dancers performing without a central conductor. Each dancer knows their role and reacts to the actions of the others. In the choreography-based saga, this works the same way via events:

- The

Order Servicecreates an order and publishes anOrderCreatedevent. - The ‘Payment Service’ listens to this event, processes the payment and publishes a ‘PaymentSuccessful’ event.

- The

Inventory Servicereacts to this and updates the inventory.

This approach is decentralized and flexible. It is easy to implement if there are few participants. However, with complex processes it can quickly become confusing to understand the entire process flow.

2. Orchestration

Here, as in an orchestra, there is a central conductor - the orchestrator. This is a separate component or process that controls the entire flow of the saga.

- The orchestrator receives the original request (e.g. “place order”).

- He calls the

Order Serviceto create the order. - After successful feedback, he calls the ‘Payment Service’.

- He then contacts the “Inventory Service”.

The orchestrator knows the entire flow, manages the state of the saga and decides which step to execute next. This makes the process explicit and easier to monitor, but also introduces a key component that could become a bottleneck.

The Key Component: Compensating Transactions

What is special and challenging about the SAGA Pattern is how it deals with errors. Since we don’t have a comprehensive, atomic transaction, in the event of an error we can’t simply roll everything back as if nothing had happened. Instead, we need to actively roll back the local transactions that have already completed successfully. This is exactly what compensating transactions are for.

A compensating transaction, as the name suggests, is an action that neutralizes or reverses the effects of a previously executed local transaction. It ensures that the system returns to a consistent state even if there is an error in one of the saga steps.

Let’s go back to our eCommerce example:

- The

Order Servicecreates the order with the statusPENDING. (Local transaction A successful) - The

Payment Serviceis attempting to process the payment.

- Scenario 1: Payment successful. The saga continues.

- Scenario 2: Payment Fails! Now we have a problem. The ‘Order Service’ has already created an order, but no payment has been received. This is where the saga needs to be undone.

In this error case, the compensating transaction would be triggered:

- The

Order Servicemust cancel the previously created order or set it to the statusCANCELLED. (Compensating transaction for local transaction A)

Another example as the saga continues:

- The

Order Servicecreates the order. - The

Payment Serviceprocesses the payment successfully. - The

Inventory Serviceattempts to reduce inventory.

- Scenario 3: Inventory reduction fails! Maybe the product is currently out of stock or a technical error occurs. Now we have an order and a successful payment, but no reduced stock. This is still an inconsistent state.

Compensating transactions also come into play here:

- The

Payment Serviceneeds to cancel or chargeback the payment made previously. (Compensating transaction for local transaction B) - The

Order Serviceneeds to cancel the order or set it toCANCELLEDstatus. (Compensating transaction for local transaction A)

It is critical that every local transaction in a saga should have an associated compensating transaction that can neutralize its impact. These compensating actions are themselves local transactions and must be atomic and idempotent, i.e. they can be called multiple times without producing undesirable side effects.

The challenge lies in orchestrating the chain of compensations correctly and ensuring that they are carried out reliably even in the event of an error. This is often more complex than the actual forward movement of the saga.

Very good. Then we are ready to finish the first part. We summarize the key points and whet the reader’s appetite for the sequel, in which we then delve into the code.

Conclusion and outlook on part 2

The SAGA pattern is a powerful yet demanding answer to one of the biggest challenges in microservice architectures: maintaining data consistency across service boundaries. Instead of relying on complex and often impractical distributed transactions like 2-phase commits, a saga breaks down a business process into a chain of local transactions.

The key takeaways from this first part are:

- Issue: Classic ACID transactions do not work across multiple, independent databases in a microservices landscape.

- Solution: The SAGA Pattern coordinates a sequence of local transactions to complete a business process.

- Error handling: If a step in the saga fails, compensating transactions are executed to undo the actions of the previous, successful steps.

- Consistency: A saga leads the system to a state of “Eventual Consistency”. This means that the data is not consistent at all times, but ultimately consistent.

With this basic understanding we have created the basis. But the theory is only half the battle. The really exciting questions are: How do you implement a saga in practice? How do you deal with concurrency issues? And how do you ensure that the compensations are actually carried out reliably?

We will address exactly these questions in the second part of this series. There we will implement a concrete saga - either by choreography or orchestration - using Spring Boot and RabbitMQ (or Kafka) and bring the concepts we discussed here to life. Stay tuned!

![[EN] SAGA Pattern für Einsteiger: Konsistenz in Microservice-Architekturen erklärt Teil 1](/images/SAGA-Pattern-Part1-BlogHeader.png)